The Poetry of Couple Communication

Aug 14, 2017

Susan B. Saint-Rossy, LCSW

PACT Level III candidate

Ashburn, VA

www.relationship-therapist.com

Most couples who come to me identify their main problem as lack of or poor communication. Many times, couples believe that if they just learned to communicate properly, their relationship would be “fixed.” Thus, various therapeutic schools have come up with techniques (e.g., active listening, the use of “I” statements) to give order to a messy, complicated process. From the PACT perspective, these approaches can oversimplify a couple’s situation.

PACT recognizes that communication is complex, nonlinear, and multidimensional—much like poetry. Couples’ communication includes the symbolic language of words, micro-expressions, body language, tone of voice, and other elements. There is no one-to-one correlation between words and meaning, or words and intent.

Considering a couple’s communication with each other to be a poem (with all its symbolism, emotion, heightened sensitivity, and multiple layers of meaning) has helped me understand the PACT therapist’s role and therapeutic stance.

Beatrice and Mel, who are in their fifties and have been married for 18 years, came to me with communication issues as their main problem. The following dialogue occurred in our first session:

Beatrice: Happens all the time over really small decisions or incidents.

Me: (to Mel): Do you know what she’s referring to?

Mel: Yes, but I can’t think of . . .

Beatrice: Like this morning. I asked him if he wanted eggs and toast for breakfast. This one (pointing at Mel) ignored me.

Mel: (very quietly, looking at me, jaw grinding) I said it didn’t matter.

Beatrice: (loudly, with movement in all four limbs) You said it didn’t matter after I asked you at least three times.

Mel: You know what I like for breakfast. So why do you ask? Besides, I can make my own breakfast. You don’t need to make breakfast for me.

Beatrice continued to discuss, with great intensity, how angry she gets when this kind of thing happens. Mel continued to downplay the event, saying Beatrice can get upset about almost anything he does or doesn’t say or do. He just didn’t want her to fix his breakfast. What’s the big deal?

Before I was a PACT therapist, I would have probably lost my patience in this situation. I may have even interrupted because I thought it was going nowhere. Now I know that my job is to look for symbolism; imagery; and evocative language in the words, voice, and nonverbal expressions—to let the poem unfold. I wait, watch, and listen. I take in the emotional tenor of the moment without becoming part of it. I “read the poem” to get my inspiration about what is going on and what to do next.

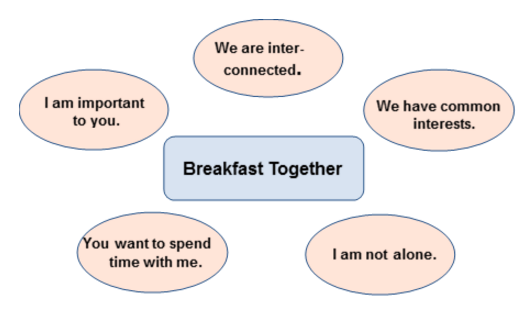

In this case, I saw that, for Beatrice, asking Mel what he wanted for breakfast is an expression of her wanting to have breakfast with him. Unfortunately, Mel didn’t realize that breakfast is not just breakfast to Beatrice, but is symbolic of much that Beatrice feels she is missing in the marriage.

In poetry, a symbol is an action, object, word, or phrase that takes on a different meaning(s) that is deeper and more significant than the original. In my aha moment with Beatrice and Mel, my contribution to their poem became clear: I could help them understand the richness underneath their communications, as illustrated in this graph:

Just as a student of poetry looks at theme, structure, symbolism, cadence, rhythm, the poet’s life, and any other applicable variables, as a therapist, I take in all the couple’s the words, voices, facial expressions, and movements, as well as my own emotional responses. My inspiration comes, and I decide how I can help shape the poem to take the couple to a more safe and secure-functioning place.